We’re republishing this column by the late Roger Di Paolo, part three of his Black History Month series from earlier this year.

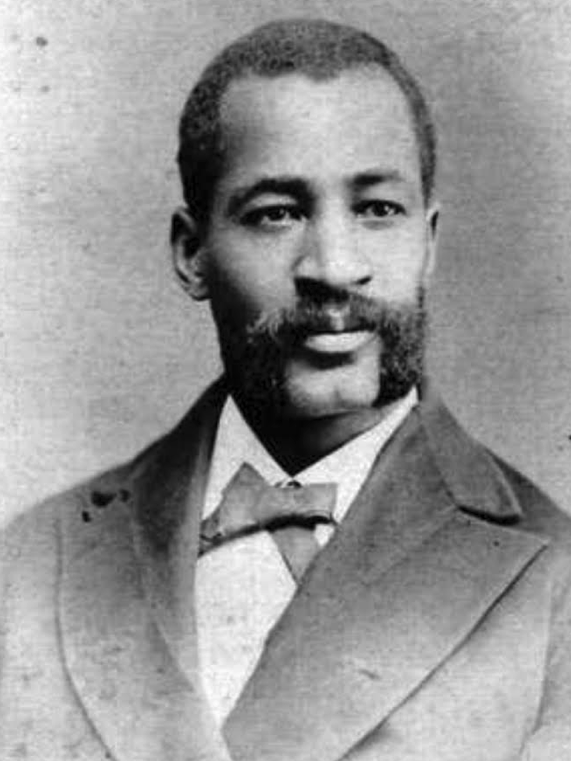

Born in a log cabin in Charlestown, Frederick Jeremiah Loudin was destined to lead a life that was anything but provincial.

He toured the globe, singing before Queen Victoria and other heads of state and enjoyed a lifestyle that included a taste of the best of the Gilded Age in the late 19th century.

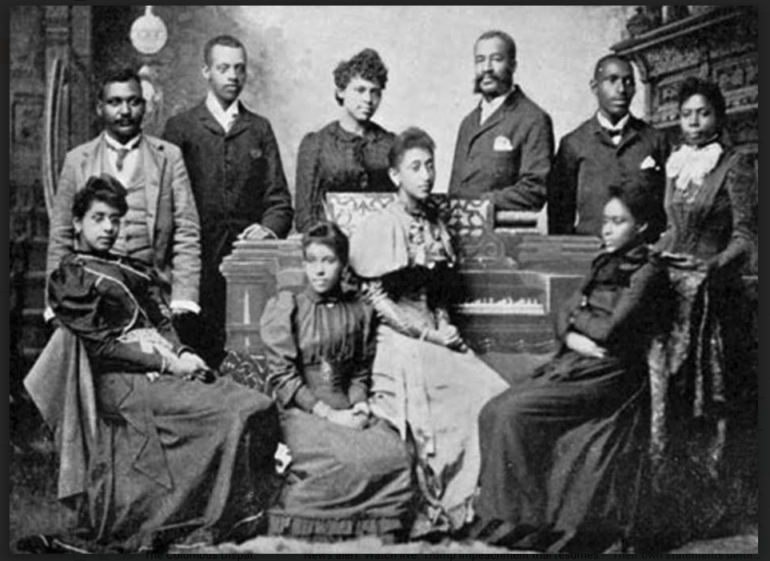

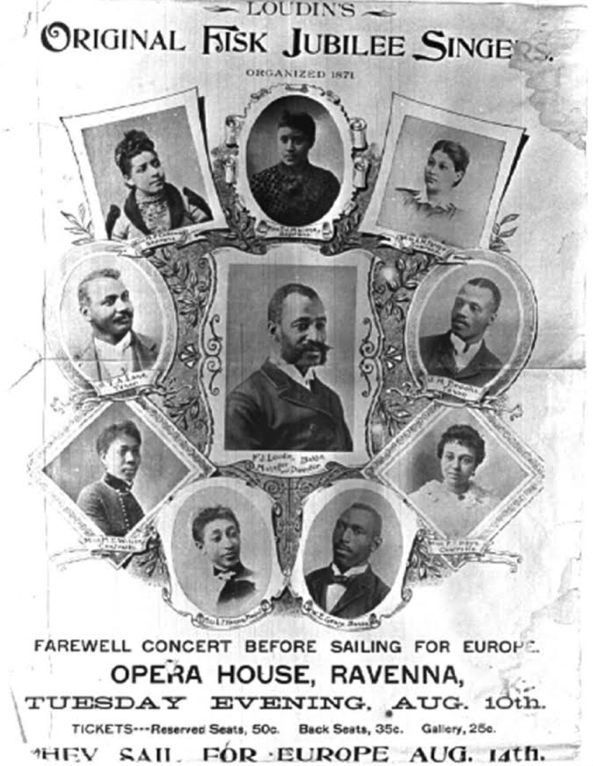

The leader of the Loudin Jubilee Singers, an off-shoot of the renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers, he was blessed with an incredible baritone voice that stood out in the African-American music ensemble.

He also had a strong voice when it came to the racial discrimination that he and his fellow performers endured during their travels in post-Civil War America, and he didn’t hesitate to raise his voice against the racism of his native country — stating bluntly in letters to Ravenna newspapers that he never knew what true freedom was until he left America and toured Europe.

His message was forthright and courageous. So, too, was the fact that it found its way into print in Ravenna only a decade after the Civil War.

Frederick Loudin’s parents, Jeremiah and Sybil Loudin, were freemen who settled outside Ravenna in 1828. Their son was born in Charlestown on June 27, 1836, and began school there. Sybil wanted her son to have a better education and moved her children to Ravenna in 1851, where a large consolidated school had been built. Frederick earned a reputation for being one of the brightest students in his class but was shunned because of his race.

After completing his schooling, he learned the printing trade and went to work at The Reformer, a short-lived anti-slavery tract published in Ravenna. Seeing little future as a printer, he moved to Pittsburgh, where he married Harriet Johnson in 1870, then settled in Nashville, Tenn., where he found an outlet for his musical talent with the renowned Fisk Jubilee Singers (even though he never attended Fisk University).

The Fisk ensemble included former slaves and freemen who sang classical music as well as African-American spirituals and gospel music. As a member of the Jubilee singers, Loudin took part in a three-year tour of Europe that included Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Ireland and Great Britain.

The troupe’s experiences in London in 1875 made a lasting impression on Loudin, which he shared with readers of the Portage County Republican-Democrat, the leading newspaper in the Ravenna area.

He didn’t mince words.

Loudin wrote that he had experienced the true meaning of freedom far away from his homeland.

“The three months I have spent [in England],” he wrote, “have convinced me that I didn’t realize my own blindness. And now I affirm that no black man born and raised in the United States of America can realize what it is to be absolutely free.”

He contrasted his experiences in Europe with the racism he endured at home.

“Think what it would be to go to any hotel, restaurant or confectionary, or any place of entertainment, and not simply to make your way … and be absolutely welcomed, no better but just the same as any man who pays his money. Not to be stuck away in some hole or corner, lest one of the other customers will see you and become indignant because a n — r’s money pays for just the same as his does.”

In London, he wrote, “the clerks do not all suddenly get too busy to wait upon you” nor did women passing on the streets draw aside their dresses “lest you black it.”

In America, he wrote, the Jubilee Singers were often the targets of bigotry, even in supposedly liberal places such as Oberlin, where white choir members insulted them when they performed for a gathering of clergy.

He also remembered the scorn he felt, years before his involvement with the Jubilee Singers, when he was forced to pose as a slave traveling with his master to obtain lodging in Cleveland and when no printer would hire him as an apprentice. He also was barred from singing in the Methodist Church choir in Ravenna despite tithing a substantial amount of his paltry wages as a pressman, and was refused admission to Hiram College because of his race.

The singers too encountered racism when they returned to the United States. Invited to sing at the White House by the wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes, they spent much of the night inquiring for lodging at several hotels in Washington, D.C., finding rooms in the pre-dawn hours at a segregated boarding house and taking their meals in a dining area separate from white patrons.

Small wonder that he preferred England, where “no one was there to insult us or in any way make us feel uncomfortable,” to his own country.

After the Fisk Singers disbanded, Loudin formed the Loudin Jubilee Singers and again went on the road, first touring the United States and Canada from 1882 to 1884, then embarking on a six-year global itinerary that began in the British Isles, made its way via steamer to Australia, with stops along the way in Egypt, India, Burma, Ceylon, Hong Kong , China and Japan. They performed in Australia and New Zealand for three years.

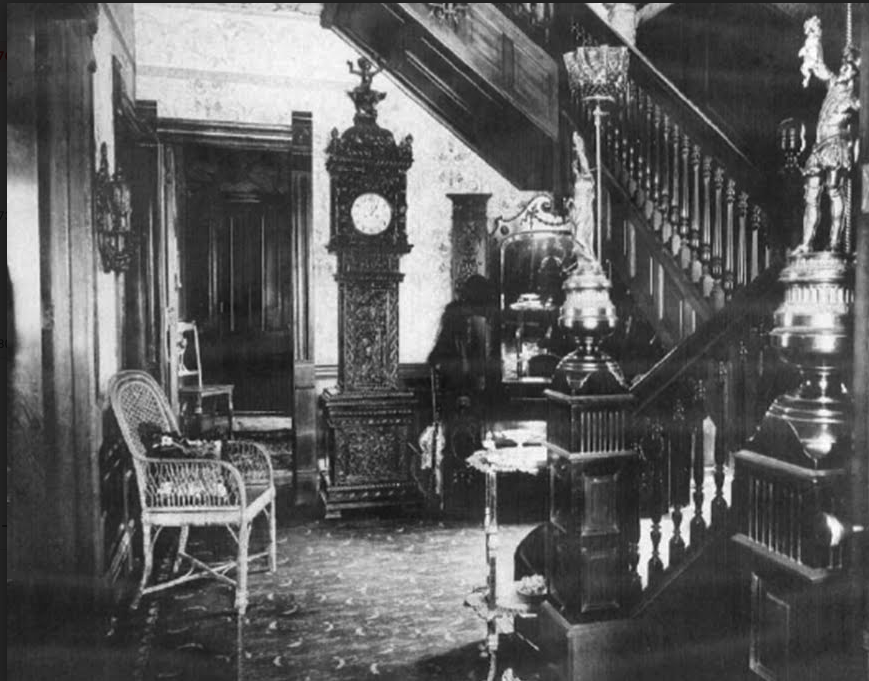

Frederick Loudin and the ensemble became wealthy as a result of their travels. In addition to the usual souvenirs, he and his wife acquired furniture and art objects as well as rare wood that he shipped to Ravenna. These were incorporated into “Otira,” the home he built at 401 S. Walnut St. in 1890–91. (Otira, which cost $3,000, the equivalent of $87,000 today, still stands.)

His return to Ravenna coincided with forays into business ventures, notably a shoe factory, which opened in a three-story building on South Prospect Street in 1892, with a business plan geared toward producing footwear for African-Americans. It employed an integrated workforce, making 300 pairs of shoes a day, but failed.

He also was an inventor, securing patents on fastening devices, including a modern forerunner of the keychain.

He remained outspoken on civil rights, taking part in national anti-lynching campaigns and attending the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900.

He embarked on what proved to be a final tour that was cut short when he collapsed in Scotland in 1903. He returned home to Ravenna, where he died at his beloved Otira on Nov. 3, 1904.

Roger DiPaolo is a Portager columnist and a member of the advisory board. He was editor of the Record-Courier from 1991-2017.