Megan Foreman is looking for her family.

She knows her father’s folks, the Derthicks and the Kuchenbeckers, helped to settle Portage County back in the 1800s, but where are they now?

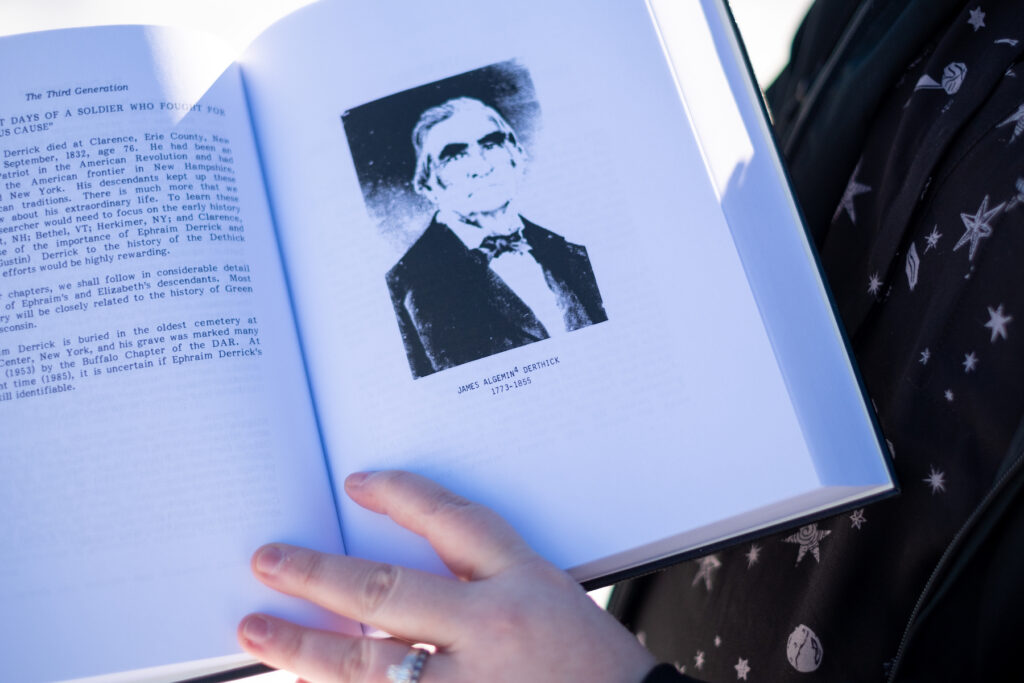

Where is great-great grandfather Jesse James Derthick, who was born in Freedom Township in 1874, and may — or may not — have been laid to rest in Fairview Cemetery in Hiram in 1953? Where is James Algemin Derthick, Megan’s five-times great-grandfather? Records from findagrave.com and her grandfather’s family genealogy book suggest he is buried in Hillside Cemetery in Shalersville, but there is no grave marker. His wife Huldah Derthick does have a stone, as does his bachelor brother, John Turner Derthick, but the trail goes cold there.

Records and gravestones have disappeared or maybe never even existed.

It’s a common story.

There are almost 100 cemeteries in Portage County, most of them shrouded in mysteries that can stop modern-day genealogists in their tracks. Even findagrave.com’s information isn’t always accurate, Foreman said.

“I think you have to know where you’ve come from to know where you’re going,” she said. “I like to feel a connection to the past. I think being able to know my ancestors’ names and their stories gives me that connection.”

Searching for the past

Foreman found a Henry Dethick (the R was added at some point after the family immigrated to America in the 1600s) who was at one point Lord Mayor of London. Another branch of the family tree turned up Hazel Derthick, who played a munchkin in the original Wizard of Oz movie. Foreman even obtained a formal photo from the Hollywood studio.

She traced the Derthicks back to 12th century England, where she found Dethick Manor, her family’s ancestral manor house in Derbyshire. It’s now a bed and breakfast, and visiting is one item on Foreman’s bucket list.

“Those were real people who had feelings, and their own emotions, and their own stories, and I’ll never get to meet them, but I can do what I can to learn about them, to try to imagine what their life was like,” she said.

It’s not easy. Slogging through the sands of time is not for the faint of heart, even with online help, genealogical groups, and sometimes even history books.

Deaths were scarcely recorded until the late 1860s, when Ohio township trustees were required to file the information with the state at the end of each year. Some did and some didn’t, and the records were only as good as the officials who kept them.

They sometimes disappeared altogether, perhaps as a clerk took them home and for whatever reason never returned them, said Barb Petroski, president of the Portage County Chapter of the Ohio Genealogical Society.

Cemetery sextons kept the records for city dwellers, but even they may have been incomplete or lost, she said.

How to lose a grave

Rootstown’s Old Cemetery, sometimes called Ye Olde Cemetery, is a two-acre plot that can be seen from Tallmadge Road, with access off the north dead end of West Drive. It was established in 1809, shortly after Rootstown became a township, said Terri Fassnacht, a charter member of the Rootstown Old Cemetery Restoration Committee. (They’re on Facebook.)

“In the mid-1800s the sexton took his cemetery records home for safekeeping. Ironically, his house caught fire, and all the records were destroyed and were never recreated,” she said. “The cemetery was ultimately closed to new burials because there were no records to determine where empty burial plots remained.”

Death certificates were mandated in 1908 but, again, were only as good as the relatives, neighbors and physicians who filled them out, Petroski said.

Further complicating the job of modern sleuths, families who lost multiple loved ones — mostly children during epidemics of measles or influenza or the like — sometimes buried multiple children in one grave, with or without noting the information.

Even when a grave marker is found, that is no guarantee that the person is actually buried there.

“My father-in-law, we have a placard by his parents’ stone in Newton Falls — but we have his ashes. So it says he’s there, but he’s not actually there,” Foreman said, adding that findagrave.com needs to correct the mistake. She’s notified the webmaster, but the error remains.

At each graveyard, weather and time take over, slowly wearing down the words on each stone until many have become almost impossible to read. Vandals accelerate the destruction, somehow finding joy in toppling the ancient headstones or removing them altogether.

Keep the cemeteries alive

Due in part to those vandals, Rootstown’s Old Cemetery Restoration Committee is trying to identify possible unmarked graves, but they need funding to continue, Fassnacht said.

With the records burned or lost, there is often no way to know where the stones should go, Petroski said.

Sometimes it takes detective work. When questions arise about people buried at Hiram’s Fairview Cemetery, assistant village administrator Steve Schuller turns to original township records or state deeds that date back to the Revolutionary War. Schuller said he’s been with the village since 2016 and has been able to identify every decedent so far.

Nelson Township officials weren’t as lucky. The trustees had to close four of the township’s five cemeteries because records, and sometimes even grave markers, simply don’t exist.

It wouldn’t be good, Trustee Anna Mae VanDerHoeven said, to dig down and discover the gravesite is already occupied.

Wherever the graveyards are, local officials do their best to maintain them. The grass is mowed, and toppled gravestones respectfully stacked, if nothing else.

The Portage County Historical Society keeps a record of each graveyard, and the Genealogical Society does its best to create and preserve local records, making them available for public use.

“The best source for information on Portage County Cemeteries is at the Portage County Historical Society,” Petroski said. “All the cemetery books, which the genealogy chapter did over a number of years, are at the Society.”

Thanks to websites like ancestry.com and numerous “roots” television shows, genealogical research has become a major hobby, Petroski said. People want to know where they came from, and genealogical societies can help fill gaps that family lore has forgotten.

“If I wanted to know where my ancestor is buried, it’s easier to have the records already there that someone else has done so I don’t have to go traipsing across the country trying to find it,” she said.

Preserving Kent’s pioneers

Kent’s Pioneer Cemetery is a local tourist destination, particularly for amateur historians, who come to study the gravestones and the stories behind them. And most have no idea that the two-acre plot on Stow Street is cared for by the small but dedicated Pioneer Cemetery Preservation Group.

Depeyster, Haymaker, Rhodes, Ruggles, Wolcott, Woodard, Clapp and Kelso are some of the names on the weathered stones. Established in 1810, about 240 people are buried there, said Chris Schjeldahl, a member of the group.

Eva Haymaker was the first recorded death in Franklin Township, which at the time included Kent. Haymaker’s family set aside the two acres surrounding her burial site to be used for a community cemetery. The parcel was later deeded to Franklin Township. The last burial at Pioneer Cemetery was in 1914.

Through its “Adopt a Pioneer” program, preservation group volunteers maintain their assigned plots at least every fall and spring, weeding, mulching and providing the perpetual care due to Kent’s ancestral families.

Despite the volunteers’ best efforts, gravestones at Pioneer Cemetery are deteriorating.

Schjeldahl said old materials, such as sandstone, cannot be protected from weather and damage. Also, once a cemetery is closed to burials, it no longer generates income needed for care and maintenance.

It has become difficult, or impossible, to know who exactly is where. At one point a boy scout, whom Schjeldahl could not identify, created a cemetery map as part of his Eagle Scout project. However, even that map seems to have disappeared, and others contain conflicting data as to where graves might be, said Nancy Stillwagon, secretary and treasurer of the preservation group.

“We’ve never done a real scientific study of where the burial spots are,” Stillwagon said.

Ground penetrating radar could detect coffins, caskets and vaults; identify ground structures and excavation features; and can “see” movements or voids caused when burial containers collapse.

Stillwagon estimated the cost of such a study at between $2,000 and $5,000, funds the group simply does not have. Without the money, volunteers are concentrating on maintaining past improvements and making sure the known sites are in good shape, she said.

With only six or seven members left, “we would love to have volunteers,” she said. “We’re in need of people who want to take pride in Kent, and the conservation and preservation of some of these old monuments.”

An added incentive: beer and pizza figures into the autumn clean-up, Stillwagon promised.

For Foreman, the search that started with a “family tree” assignment in elementary school continues.

“I honestly don’t know if I’ll ever be done,” she said. “For me it’s still learning the story. I want to know more than names and dates on a page. I want to know about their day to day life.”

Wendy DiAlesandro is a former Record Publishing Co. reporter and contributing writer for The Portager.