A good writer can make a bit of history read like a suspense novel. Both these books show how true this is.

“The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder” by David Grann tells the true adventure of castaways from HMS Wager, a British man-of-war lost at sea in the 18th century.

In 1740, about 250 officers and crew left Portsmouth on the Wager among a squadron of ships on a secret mission: “The heart of the plan called for an act of outright thievery: to snatch a Spanish galleon loaded with virgin silver and hundreds of thousands of silver coins.” The ship was hit by a hurricane near Cape Horn and went down off the Pacific coast of Patagonia; 81 men, floating on ship’s wreckage, made it to shore on a desolate island.

Grann begins the account with some background on ships and the life of a sailor. His writing puts the reader in the setting: “The cobblestone streets past the shipyard were congested with rattling wheelbarrows and horse-drawn wagons, with porters, peddlers, pickpockets, sailors, and prostitutes. Periodically, a boatswain blew a chilling whistle, and crewmen stumbled from ale shops, parting from old or new sweethearts, hurrying to their departing ships.”

The wooden ships were extremely vulnerable. They could be burned or sunk, of course, but they were also easy victims of a wood-devouring fungus, deathwatch beetles, termites, and “a reddish shipworm, which can grow longer than a foot.” A ship could suddenly just spring leaks, take on water, and sink. It happened.

Then there was shipboard life. Grann explains what some of the work at sea entailed and notes “an inescapable truth of the wooden world: each man’s life depended on the performance of the others.” As for the seamen, they were subject to all manner of diseases in the close quarters, and long voyages often meant the men developed scurvy. The descriptions of scurvy symptoms are a horror show. Many men didn’t even want to be there; they were press-ganged — kidnapped and locked in the holds, “which resembled floating jails.”

The survivors of the shipwreck found their island inhospitable, and there was almost nothing to eat. The leader of the castaways tried to maintain order on their island, but the group broke into factions. Facing “starvation and freezing temperatures,” some men sank to a “state of depravity,” committing theft of the little stores they had, murder, and even cannibalism. Think “Lord of the Flies.” Grann writes, “The forces unleashed on Wager Island were like the horrors inside Pandora’s box: once unlocked, they could not be contained.” How they survived takes on the elements of a thriller.

The men left the island eventually, in different groups. How any managed to return to England years later seems like a miracle. The first group to arrive at home leveled charges of mutiny against their shipmates. When a second group got to England, there were “charges and countercharges from both sides” with “wildly conflicting accounts” of what happened on Wager Island.

Grann is such a great author, he makes nonfiction read like fiction. If you haven’t read his outstanding “Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI,” do look it up. It’s one of my all-time favorite nonfiction books. Seriously. It may even be my favorite. Martin Scorcese has made a movie of it, which will come out later this year. But read the book first, by all means. It’s an experience you won’t want to miss.

For a fictional account of the adventure of HMS Wager, read Patrick O’Brian’s “The Unknown Shore.”

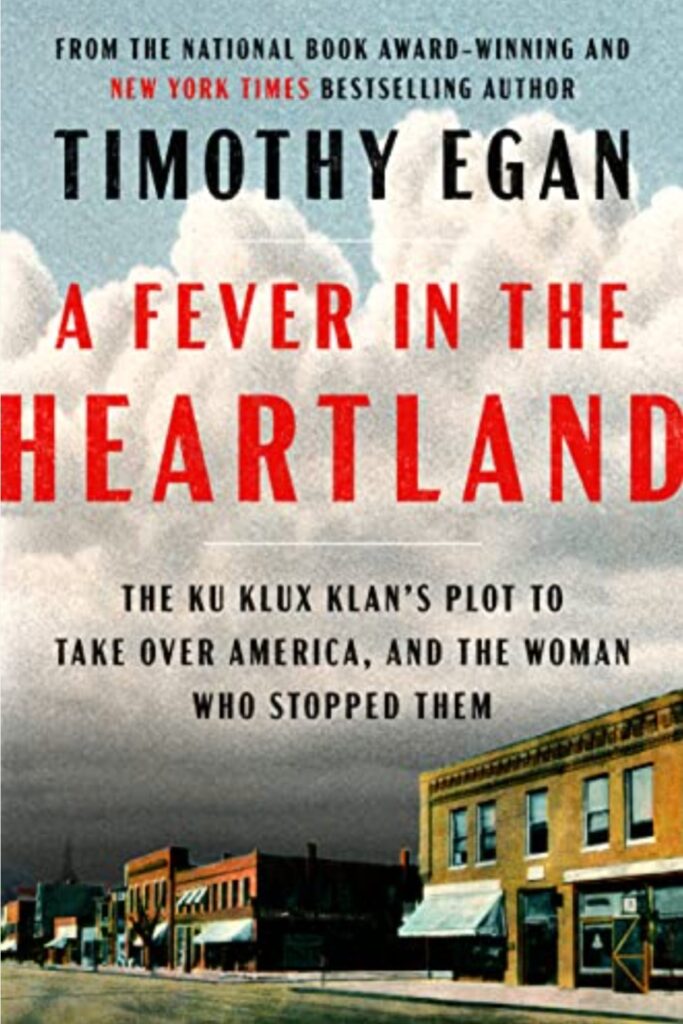

“A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them” by Timothy Egan is a well-written history of the growth of the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana and other northern states in the 1920s. The book centers around one man: D.C. Stephenson, who became the most powerful man in Indiana. Through greed, cunning and deceit, he quickly worked his way up to Grand Dragon of the Klan. Always bragging “I am the law,” he could get away with almost anything — except one woman’s death.

Egan summarizes the rise and fall of the Klan in the 1860s and goes on to describe the growth of the “new” Klan in the 1920s, which blossomed “with the blessing of Protestant clergy.” Oh, yes, many “good” people joined the ranks as the movement spread to the North. They were newspaper editors, judges, police, “bankers and merchants, lawyers and doctors, coaches and teachers, servants of God.” By day, the Klan was known as a civic-minded and even charitable group. Members held pride parades. “Their wives belonged to the Klan women’s auxiliary, and their masked children marched in parades under the banner of the Ku Klux Kiddies.”

Why the 1920s? Some 200,000 Black soldiers had fought in World War I and, on their return, “felt entitled to be full citizens,” but the white establishment said no. The Klan believed in eugenics, and members took an oath “to maintain forever white supremacy.” Most really thought they weren’t bigoted. They just hated Blacks, Jews, Catholics, and immigrants. The Klan hired paid recruiters and grew in power until “one in three native-born white males wore the sheets,” Egan writes.

Stephenson’s audacity and charisma shot him to the top of the movement and made him rich and powerful. “I’m going to be the biggest man in the United States,” he bragged. Crowds loved him. “Some of them stretched out their arms to him like they were praying,” Egan writes. “He needed to be told that he was loved.” Stephenson “discovered that if he said something often enough, no matter how untrue, people would believe it. Small lies were for the timid. The key to telling a big lie was to do it with conviction.” He hired “poison squads,” a disinformation brigade to spread his lies. Egan tells us, the people “believed him because they wanted to believe.” He didn’t pay his creditors. When he was accused of a crime, he “compared himself to Jesus, martyr of a monumental injustice,” and said it was “the most appalling persecution to which man has been subjected.”

Stephenson was a ladies’ man, but also a bully and sexual predator who liked violence with his “romance.” When he met 28-year-old Madge Oberholtzer, he decided he wanted her. She ended up dead.

What happens to Madge is horrific and reads like a thriller. Then follows the court case, which reads like a Grisham novel.

There’s a warning hidden in the history. Stephenson claimed that “you didn’t have to lead a man to hate, just show him the way and he’d do it on his own.” He said, “I did not sell the Klan in Indiana on hatreds. I sold it on Americanism.”

Happy reading!

Mary Louise Ruehr is a books columnist for The Portager. Her One for the Books column previously appeared in the Record-Courier, where she was an editor.