This month last year, folk musician Steve Earle buried his eldest son, Justin Townes Earle.

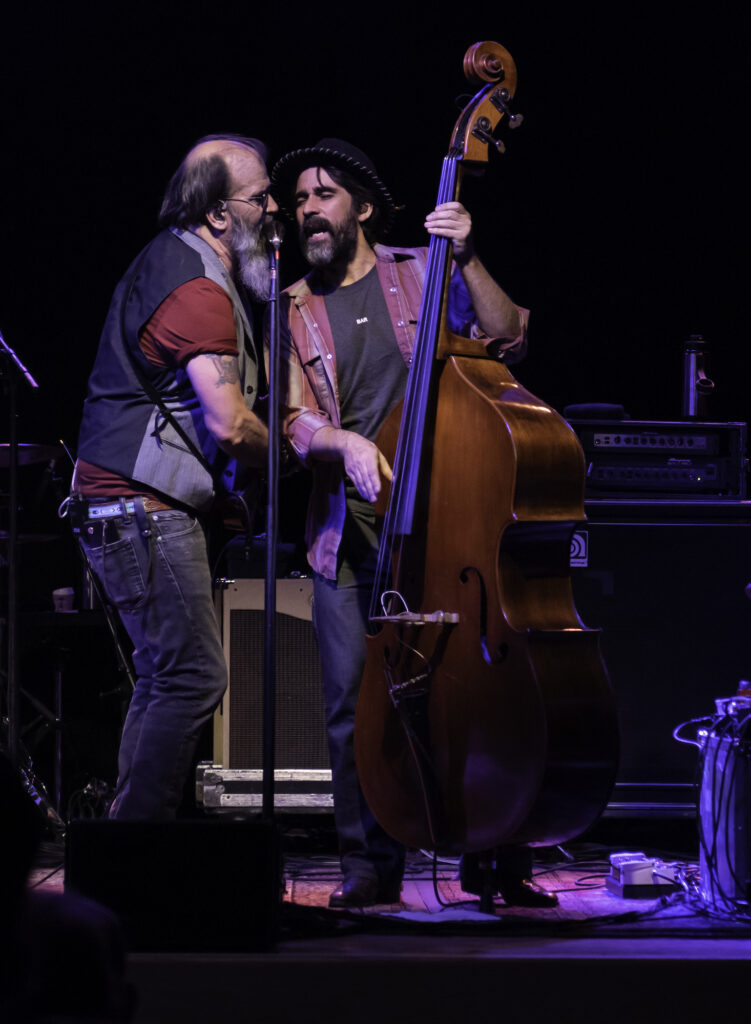

Friday night, when Earle and his band, The Dukes, returned to The Kent Stage, they remembered and celebrated Justin by playing his songs.

Earle, a prolific songwriter who rose to fame in the ‘80s with the songs “Guitar Town” and “Copperhead Road,” has made regular stops in Kent during tours over the course of the past decade.

This time fans may have wondered if Earle — touring to promote an album of his son’s covers — would deliver a more somber show. Yes and no, it turned out: The band performed all the upbeat crowd favorites and love songs, with bright mandolin and wailing steel guitar.

But Earle’s new material from J.T. and Ghosts of West Virginia, about a mine explosion that killed 29 people in 2010, took the audience to a more introspective place. Earle showed us a more vulnerable side of himself and supplied the most memorable moments of the show.

Earle’s opening act, The Mastersons, set the tone for the show both stylistically and thematically, serving up songs about grief and loss from the married duo’s most recent album, No Time for Love Songs, couched in their signature goosebumps-eliciting harmonies.

They released the album a month before “the world shut down for the pandemic,” guitarist Chris Masterson said wryly, so technically, “this is our record release tour.”

To introduce a song called “The Silver Line,” vocalist Eleanor Whitmore (who moved between fiddle, keyboard and guitar throughout the evening) said lately she had been thinking about Kelley Looney, the long-time bassist for The Dukes who passed away in November 2019, for whom the song was written.

She acknowledged that collectively, we have experienced much loss over the past year and a half, “so this one goes out to anyone who knows somebody who’s moved over to the other side.”

Whitmore’s voice is a marvel, clear and soaring, powerful but controlled, and hearing her sing a line like, “though these hands, they can’t hold you / I still feel you shining in the sun” was devastating.

Equally devastating was the couple’s performance of “King of the Castle,” a ballad about losing guitarist Chris Masterson’s father, which Whitman shared was inspired by a conversation with another musician, Rosie Flores, who observed that when her own father died, “it was like the king of the castle had gone.”

Not all the songs in The Mastersons’ six-song set were somber, though. “This song is the perfect song for a married couple stuck at home for a year — it’s called ‘Fight,’” Whitmore quipped before the two launched into an entertaining performance that sounded remarkably like a fight, instrumentalized: The fiddle lamented and the pair crooned “What we gonna do-oo-oo-ooh?” before culminating in a farcical duel between Masterson’s guitar and Whitmore’s fiddle.

None of the performers shied away from talking about Covid, and Masterson took a playful approach, saying, “This show has been brought to you by the fine folks at Pfizer.” As Earle implied when he introduced the couple, all musicians now are relying on people getting vaccinated so they can make a living on live shows.

“So don’t fuck up,” Steve barked at the audience jokingly — notably, the same piece of advice he gave at The Music Box Supper Club ahead of the 2016 presidential election.

Masterson and Whitmore left the stage only to return with the full band for Earle’s set, while “Happy Days Are Here Again,” an old-timey tune famously used for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1932 presidential campaign, played over the speakers. Along with the song, the hammer, sickle and skull on the bass drum and The Dukes’ wardrobe choices — jeans, vests, cowboy boots, ball caps, and bandanas — harkened back to a different era.

The first nine songs exploded off the stage, sounding big, the way you’d expect from a band that has been together for decades. Earle’s harmonica and mandolin, Whitmore’s fiddle and keyboard, and Ricky Ray Jackson’s pedal steel added texture to old favorites like “Feel Alright,” “Guitar Town” and “Galway Girl.”

The first third of the show closed with the crowd favorite, “Copperhead Road,” which sent people to their feet whooping and clapping during the bagpipe intro. Several people went down front to dance, despite The Kent Stage’s guidance against gathering by the stage.

Earle introduced the middle portion of the concert by saying the band released two albums last year: “The one we made on purpose, and the one we didn’t plan.”

Earle began working on the planned album, Ghosts of West Virginia, after playwrights recruited him to write music for an off-broadway production, Coal Country, about the Upper Big Branch mine explosion, which killed 29 West Virginians in 2010. The playwrights and Earle lifted words verbatim from interviews with the relatives of those lost in the explosion to compile the script and songs, Earle said.

“I don’t think we listen to each other any more in this country, or listen to each other’s stories,” Earle said, explaining what compelled him to join the project. For instance, “people don’t know shit about West Virginia — they don’t know it’s the most unionized state in the country.”

“Everyone grieves differently. Some people don’t want to talk at all. Some people talk a lot, because they’re angry,” Earle said to introduce the standout song from this portion of the show, “It’s About Blood.”

Earle’s own rage and indignation over those killed because of blatant safety violations the company tried to cover up were manifest at the end of the song when he boomed the 29 names of those killed while the band played the same three chords over and over again, stretching on until it felt almost painful. And that was the point.

Another Ghosts of West Virginia standout was “If I Could See Your Face Again,” which so aptly and movingly described losing a loved one that I wondered if Earle had written it after his son died. (He hadn’t.)

Earle said he “almost immediately” decided to record J.T. after Justin’s death — not for his son’s sake, but for his own, to help him process the loss. Earle had wanted to release the album in time for Justin’s birthday, which was five months away, so he recruited his son and Justin’s half-brother Ian to go through the eight albums Justin wrote over the course of a decade to narrow the list down. From those, Steve selected 10 to record and added one original song, “Last Words,” to the batch.

Earle opened the Justin portion of the show with “Far Away In Another Town,” singing a capella over an organ effect played on the keyboard, which transported the audience from concert hall to cathedral, sitting as if for a funeral in hushed reverence.

He followed that song with “Saint of Lost Causes,” a song a Pitchfork reviewer questioned if Earle should have included on the record, saying it felt “weirdly out of place” for its “brimstone sermonizing.”

On the contrary, for Coal Country, Earle spent months stepping into mourners’ shoes — now, as a mourner himself, Earle stepped into Justin’s headspace and sang about the despair Justin had felt in those dark years before his death.

The song that may have seemed out of place was “Harlem River Blues” — an upbeat gospel-infused song about drowning that put Justin on the map in 2010 — which seemed flippantly and distressingly celebratory in contrast with the earnest grief the performers expressed earlier.

Then again, maybe it was absolutely fitting for Justin to prophesy his own death (right down to the lyric, “Give my money to my baby to spend”) and for his father to honor it (proceeds from J.T. are for Justin’s daughter). The song ended with Masterson, Whitmore, Earle and bassist Jeff Hill singing the chorus a capella, and in the silence following the song, someone said, “Thank you, Justin.” Others clapped appreciatively.

“Justin Townes Earle’s songs were as good as anyone’s,” Earle told the audience, his pride for his son obvious, “and they were pretty fucking good.”

Earle and The Dukes closed the final third of the show with two love songs (“You may have gathered we arrived at the chick portion of the set,” Earle said) and a handful of big anthems that hit on themes that had became canon for both Earle and his son: bad choices, un-outrunnable demons and death.

Lyndsey Brennan is a Portager general assignment reporter. She is completing her master's degree in journalism at Kent State and is an alumna of the Dow Jones News Fund internship program. Contact her at [email protected].