Community groups in Mantua Township have invested thousands of hours of their time into turning the Mantua Center School into a vibrant community center: volunteering physical labor, writing grants and proposals, hosting fundraisers and chairing committees.

Yet two decades after the township acquired the building and at least nine years after the building was cleared for occupancy, it sits mostly empty. Many of those community members say it’s because the township trustees, two of whom have been in office for about a decade, have not followed through on their promises to make use of it.

When he ran for re-election in 2015, chairman John Festa said restoring the school was a priority and had always been “at the top of my list.”

“There’s no effort for anybody to sell or destroy the building,” said Festa, who entered office in 2011. “The trustees are all for the school. We want to get this done, and we are well on our way.”

Trustee Jason Carlton, who was elected in 2009, expressed similar sentiments at a 2013 trustees meeting, according to meeting notes from a local activist. “I am absolutely in favor of [putting] offices in the building,” he said. “I am absolutely in favor of keeping records in the building. Those are primary concerns. We need to get that building useful as soon as possible.”

Volunteers say Festa and Carlton’s actions demonstrate otherwise: When potential tenants, such as a daycare owner or a church group, approached trustees about renting portions of the building long-term, generating potential revenue to offset the cost to maintain the school, the trustees blocked their plans or stalled.

While groups have rented out the school building for short periods over the years to host soup suppers, art walks or a clothing giveaway, the only permanent use trustees have found for the space is as the fiscal officer’s office, even though the township is paying for utilities, insurance and property taxes on the entire building.

Trustees John Festa and Jason Carlton declined requests from The Portager to discuss the Center School prior to a Thursday meeting where the school is on the agenda. Carlton also said he was not well-versed on the issue, despite 11 years as a trustee. The Portager sent the trustees a written list of questions and received no response.

The trustees have made some progress. They spent the past five years working to install a gurney-style elevator that cost over $200,000 with the aim of bringing the entire structure in line with Americans with Disabilities Act guidelines. A different set of trustees brought the gymnasium and the warming kitchen in the annex into ADA compliance a decade earlier.

But after 17 years, multiple studies, special meetings, committees and a task force, some residents expressed anger and frustration that the building remains empty.

“It just makes me sick to even think about it — that we, a little handful of volunteers, made such a huge effort to make that school so it could work from basement to top floor, and it is now just going to wrack and ruin,” said Mantua resident Terri Vechery, who played a pivotal role in rechartering the Mantua Restoration Society.

A new chance to take action

Now, the restoration society is making another push. They have brought forward a plan to make the main floor of the original building fully functional and occupied, with one classroom as a dedicated gathering place for community groups and the others as offices and storage for township records.

On July 1, Mantua Restoration Society member Carole Pollard presented a formal proposal to the trustees with next steps and estimates for repairing the heating system, replacing the windows, refinishing the floors and painting the walls. The society would kick in its own funding and seek grant money to cover the costs.

All the trustees would need to do is approve the plan and allow them to begin applying for grants, Pollard said.

At their next meeting, at 7 p.m. Thursday, trustees plan to discuss hiring a firm that specializes in historic buildings to conduct a cost analysis.

“I believe it will be a worthwhile opportunity for us both to ask and answer pertinent questions and share ideals, and what a better way to do that than at an open meeting held in the public forum,” Festa said in an email.

“We’ve always found it highly beneficial to have these types of publicly held discussions as a way to separate fact from misinformation. It also allows us to present an honest accounting to the Mantua Township residents and the entire Mantua community,” he said.

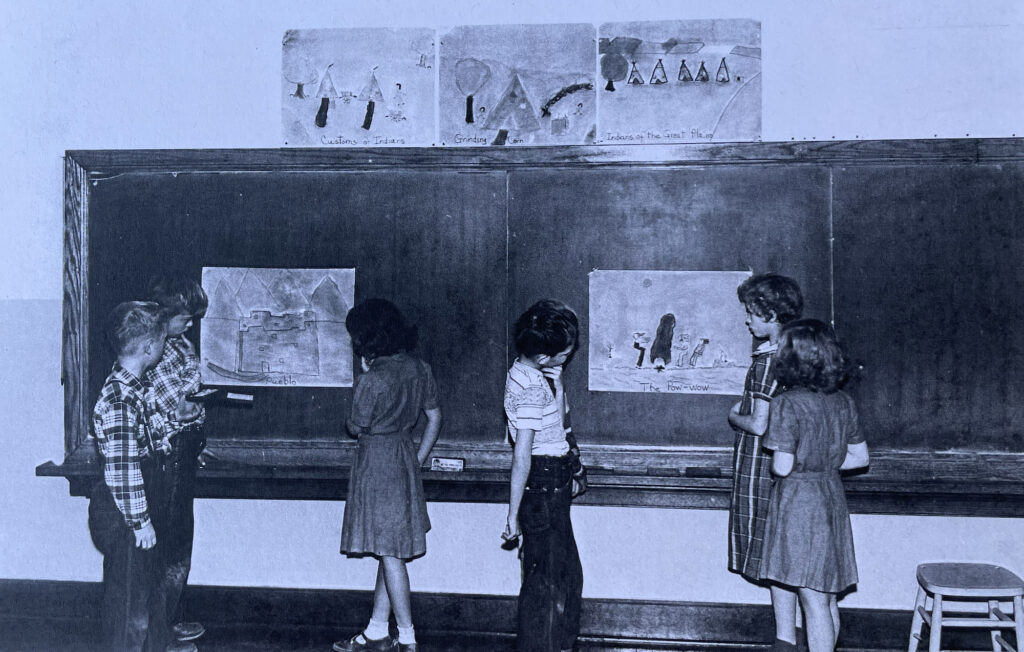

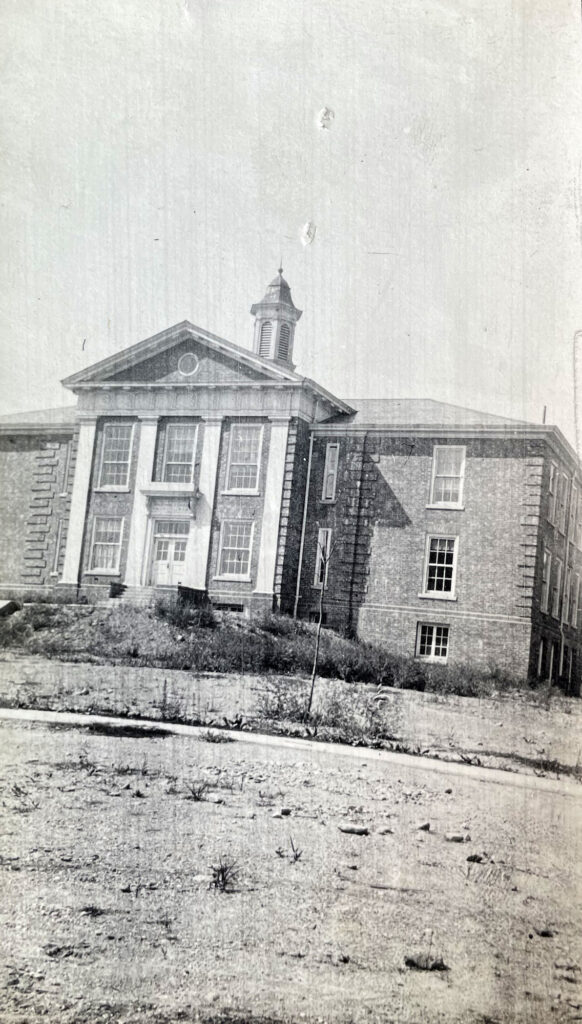

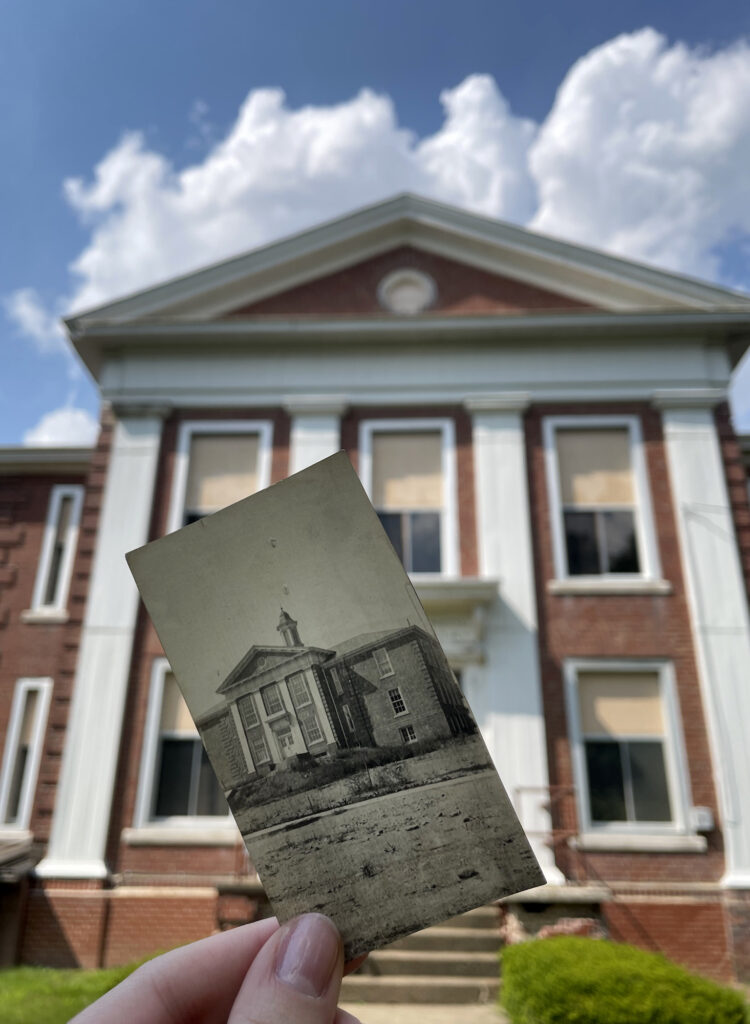

Built to last

Architect Paul Cahill was enlisted to build Mantua’s Center School in 1914. Following a deadly 1908 fire in Collinwood, near Cleveland, that killed 172 students and two teachers, Cahill prioritized safety. The school was “built to last,” Pollard said.

In 2004, the Crestwood School District announced it was going to consolidate, build new schools and sell off the smaller, older ones. Mantua Township trustees decided to acquire the Center School for $147,000 and took full possession of the building in 2006.

Before they bought the school, the trustees spoke with residents in the community and “could not find 20 people against it,” said then-trustee Vic Grimm at a meeting in December 2012.

In early 2014, the trustees invited Portage County Regional Planning Director Todd Peetz to conduct a community survey that found 75% of respondents living in the area favored opening the building for community members to use more frequently. Peetz said the remaining 25% of respondents felt the building was going to be “a big cost drain” to the community.

Opponents of repurposing the school often cite a study the Crestwood school district conducted prior to the sale that found it would cost $2 million to completely modernize the building for the purpose of remaining a school.

Pollard said the $2 million figure is misleading. After consulting with vendors, the Mantua Restoration Society estimated it would cost a little over $200,000 to complete the first floor of the building, and Pollard believes a large chunk of that ($188,000) could be covered by grants.

Volunteers have already secured $349,000 in funding for past projects, said Terrie Nielsen, who co-chaired the grants and funding committee for the township.

There is a misconception among residents that the school costs the township a large percentage of its operating budget, around 80%. But restoration society treasurer Lynn Harvey said a previous fiscal officer told her otherwise. At the height of the school’s expenses, when the township was still paying a mortgage for it, the school took up 9% of the township’s budget. The cost is much less now, probably around 5%, Harvey said.

The Portager could not verify this because the township did not respond to a public records request for budgetary documents and other information. (See footnote below.)

In 2006, current restoration society president Mark Hall was elected as a township trustee and helped enact the first phase of refitting the school for use, as laid out in a 2005 building assessment performed by Kent-based firm Dave Sommers Architects. The trustees brought the gymnasium and its restrooms up to ADA compliance, did electrical work in the hallway outside the gym and prepared the lower level for occupancy by a daycare, Hall said.

The annex renovation cost the township $22,000, well below the $30,000 they had estimated it would take to fix it, Grimm said. In July 2011, a group that called itself Friends of the Mantua Center School held an open house to celebrate the completion of the first phase.

In 2012, the Friends of the School renewed a charter for an organization that had fallen dormant in the early ‘80s and became the Mantua Restoration Society. The Center School was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The same year, Hall left office.

Then Festa was elected, and momentum on renovating the school slowed.

Best laid plans

Starting in 2012, trustees consistently thwarted plans that would have brought rental revenue to the township and productive use to the school.

One of Festa’s first acts in office was to block a woman from setting up a preschool co-op in the lower level “with threats of legal action,” Pollard said.

A woman named Debby Vogias was looking for a bigger space to run a preschool co-op and had been invited under a former board of trustees to rent part of the school. They gave her permission to start loading equipment into township trailers parked next to the school, Hall said.

The preschool would have generated $6,000 annually from rent, former fiscal officer Marie Stehli told Pollard.

But then the township killed the project by selling the trailers out from under her. Carlton and Festa voted to sell the trailers, which were valued at under $2,500. And Festa contacted the prosecutor’s office for advice on what the trustees could do if Vogias would not vacate voluntarily.

In another project that went nowhere, Hilltop Christian Church Pastor Jeff Jackson and Mantua Center Christian Church Pastor Chad Delaney brought the trustees an ambitious five-page proposal in 2016 to rent the building and set up a community center. They envisioned a teen cafe, a business incubator to nurture startups, and space for organizations like the Portage County District Library, United Way, Hiram College and the YMCA of Greater Cleveland to provide services to residents. They even hired an intern who had experience launching a similar community center in Kansas.

But it never came to fruition.

After Jackson and Delaney pitched their plan on Aug. 26, the pair pressed the trustees at meetings on Sept. 1, Oct. 6 and Oct. 20 to give them concrete dates so they could begin setting a timeline for moving into the building. They received none.

The two pastors tried to work with community members to garner more support for the project. But eventually they moved on.

“There were discussions that went on, and then it just died,” Hall said, reflecting on the work Jackson and Delaney put into their proposal.

‘We can’t afford it’

In the dozen interviews The Portager conducted with people who have been connected to the school over the years — contractors, restoration society members, government employees and volunteers — several referred to the influence of one individual to stall the project but declined to name him on the record.

The man is Larry Lietzow, a well-known businessman in the community, who has led a faction of residents opposed to using the school as a community center because they deem the cost of restoring and maintaining it too financially burdensome for the township.

Reached by phone, The Portager asked Lietzow if this criticism had any weight.

“Sweetheart, you’re exactly right. I have a lot of influence in this community,” he said. “A lot of it. In fact, two of the trustees that are in there right now, I got ‘em voted in. … I have a lot of property in this community, and I have a lot in the village. I have common sense. I was a businessman for 30 years. I know right from wrong, and I know how to make a buck.”

Lietzow claimed it will cost close to $5 million to renovate the school, but he could not say what he based his estimate on and said the trustees “don’t have figures yet on that.” Lietzow also maintains it is unsafe to enter the school, in part because of asbestos in the building.

But an inspection by Diamond Environmental found “nothing of major concern,” Hall said. The trustees took care of all hazardous materials, including asbestos, which the Mantua Restoration Society paid to remove.

In 2015, the trustees hired engineer Hal Stamm to assess the building to verify whether it was safe for occupancy. Stamm’s analysis assured him that the structure had adequate strength.

“It has passed all the tests,” Harvey said. “That building is built for eternity, really. I mean, it’s very stout. Yeah, it needs work, but it isn’t gonna fall down, and it’s not deteriorated structurally.”

Rather than investing in school repairs, Lietzow said the township should focus on other priorities, like maintaining roads. The old school is “a big hole in the water to put your money in. It will always cost a lot of money, and we can’t afford it.”

“I don’t think the trustees want to open that school,” Lietzow said, contradicting the trustees’ own previous statements. “I don’t know who told you that. We’ve got trustees that don’t want that school. They want to leave it up to the public to vote on it.”

Lietzow said he would like to see the school become a parking lot. “Take a wrecking ball to it,” he said. “It’s not worth putting a dime in.” Besides, the township already has three community centers: the Knights of Columbus Hall, St. Joseph Church and the Civic Center, “500 yards from that old school that they just put a bunch of money into.”

A master plan

On the day World War II ended, a bell rang out from Mantua township. Nora Brant’s father, Carl Foster, who had been the school janitor at the time, excitedly ran up to the bell tower and “rung the bell ‘til his arm couldn’t ring it anymore,” she said.

Sixty years later, during a ceremony celebrating the restoration of the bell tower, someone from Brant’s family rang the bell again — this time, her children and grandchildren. “The idea that he did that, and that my kids could ring that bell and feel that connection to him, it’s heartwarming to me,” she said.

For much of her life, Pollard said, “old buildings meant nothing to me.” Then, she began to realize their value: “One of the things that occupying armies do, the first thing they do when they overrun a county, is they destroy its monuments and sacred buildings.”

“If you take away a people’s history, if you take away their memory, then they are open to manipulation and control, because they have no baseline. They have no foundation. That building gave any number of us — we were farm kids, it was a farm community in 1945 and ‘46 — it gave any number of us a good solid start.”

If the trustees want to show people they’re really committed to opening the building, they can reassure their constituents by adopting a master plan, said Peetz. “Anything else would be lip service.”

“When you have a plan, you have guidance … when people do pass away or when they aren’t a trustee anymore. And the community knows what should be happening,” he said.

Hall, too, would like to see trustees put a plan in writing for how they will go about making the renovations needed. During Hall’s tenure, the trustees had a road paving plan that was scheduled every five years and reviewed annually. It was a dynamic document in that it could change if other financial demands came up, but it gave direction.

Hall also wants trustees to accept the restoration society’s proposal to begin work on one of the rooms. “Once people begin using that room, they would see what the building is, how it can be used. Once people know it’s there and it’s available, then others will come along and start inquiring about it.”

Doug Fuller, a retired architect who had worked on the school with the Dave Sommers firm, said the renovations don’t have to happen at once. “You can do them step-by-step, and do the things that you have to do to get the building open. Maybe put in storm windows initially as opposed to replacing them all. But you have to just step your way into it, the way they’ve been doing. And they’ve been doing extremely well.”

Fuller said it would be “illogical” to put as much time and energy into the project as they have and not see it through to the end.

“They’ve done a huge portion of the work, by getting the elevator in there. They’ve re-done the whole roof. Tremendous progress has been made. So why stop now?”

Footnote:

The Portager submitted a public records request for the following documents to the township fiscal officer, Sue Skrovan, on July 22:

- Any proposals submitted in or around 2015 for a master plan for the school building,

- Minutes from special meetings to consider the use of the school,

- Any proposals or requests submitted by community groups or businesses for use of the school,

- Records that show what cosmetic or structural improvements were made to the building since 2004, their cost, and the group or organization that paid for the improvements.

- Records that show the dollar amount the township spent on property taxes, utilities, and insurance for the building in recent years,

- Budget documents that show township expenditures from 2018, 2019, and 2020 and reflect what percentage of the township budget is allocated to the school, and

- Estimates received by the township for fixing or replacing the building’s heating system.

The Portager made numerous attempts to follow up by phone and email but only received two of the requested records in time for publication.

Lyndsey Brennan is a Portager general assignment reporter. She is completing her master's degree in journalism at Kent State and is an alumna of the Dow Jones News Fund internship program. Contact her at [email protected].