By Anthony Catalano

The colonization of Northeast Ohio dates back to the late 1700s, including the settlement of what is now Portage County. To honor the native culture of the land we live on, it is time that our area’s townships consider where we really live.

I live in Randolph Township, and I have been investigating the pre-colonial history of this area. I believe Americans have a responsibility to be more aware of our nation’s indigenous history, and I started my research as a way to hold myself accountable. This is just one minimal step in the right direction of solidarity with Native Americans. In the process, I’ve discovered information about our community that is largely unknown to those of us living here today.

Ohio seems to conveniently brush its indigenous history under the rug. Native American history is everywhere in Ohio, but not in ways that it should be. At least now, after decades of lobbying for change, Cleveland’s MLB team finally has a new, non-racially insensitive mascot.

Several indigenous names in Ohio are also misappropriated to current towns and cities. Take for example, Brady Lake, which is named after Samuel Brady — known for being a notorious hunter and murderer of Native Americans.

The lack of awareness of Native American culture in small Portage County townships is widely overlooked and perpetuates the myth of the absence of Native American life. Now is the time to change our perspective. We need to recognize and internalize that we are living on stolen land.

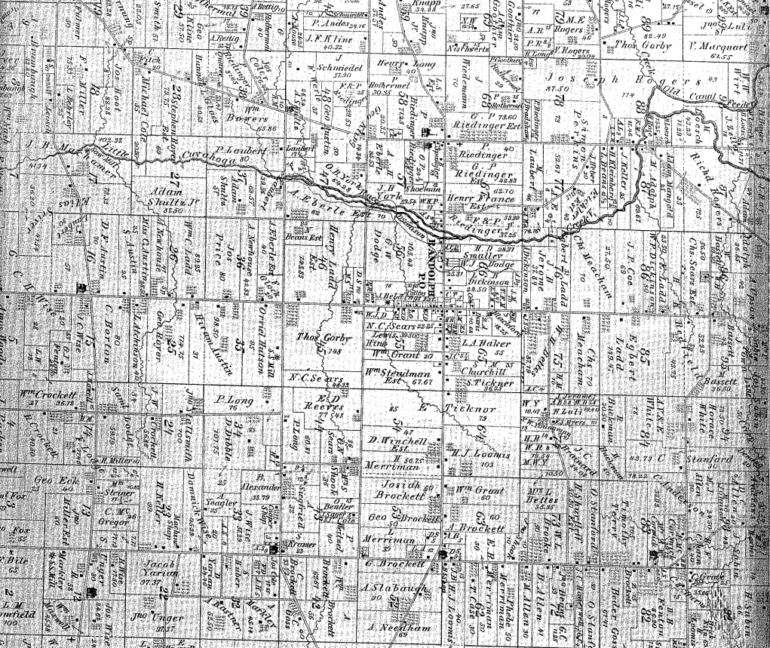

I can speak specifically to Randolph since I live here. While my township does a good job preserving its white history, I’ve yet to see any mention of Native American history included in the township’s historical narrative. This is troubling, considering the time period the township was settled.

Bela Hubbard, the settler and founder of Randolph from Connecticut, arrived in 1799. We romanticize his arrival, choosing to remember Hubbard’s claims to the Hubbard Squash, and introducing European agriculture to the township. Excluding Native Americans from Randolph’s history remains culturally insensitive and inaccurate. Hubbard was not the only resident of this area at that time.

The first resource that appeared in my investigation into the township’s indigenous history was this Portage County Genealogy site. This site explains, from a white settler perspective, the history of Native Americans in Portage County. It quotes The History of Portage County, published in 1885 by Chicago’s Warner, Beers, & Co., and edited by Robert C. Brown and J.E. Norris.

I was surprised to see a section in The History of Portage County that discussed the early history of Randolph. In this section of the text, early settler recollections claim:

“In Randolph Township, we have been informed a mound was opened some years ago which disclosed the bones of a skeleton, together with some fragments of pottery and rude stone implements. To the northeast of Hiram Center the writer noticed an elevation that bears the almost unmistakable marks of artificial workmanship, and it is believed that if excavations were made into it the usual pre-historic ‘finds’ would be the reward.”

I find this information to be important, yet troubling. This mound that is mentioned belonged to Native Americans before European colonization. The person or people who built the mound remain unknown. However, the original author put it lightly, saying the mound was “opened.” Let’s face it: The mound was destroyed, the bones cast away and the memorial desecrated. There is no way to find the physical remains of this mound today.

This is only one source, and it is presented through a white American perspective. It examines a group of people through the lens of an archaeological project, rather than from a sympathetic perspective. A sympathetic perspective recognizes that Native Americans are still here and are not cultural or archaeological relics. Sources that are sympathetic to the current lack of Native American heritage in Portage County, rather than explaining how they were simply overtaken and discarded, need to be at the forefront of this discussion.

I found a second source from this time period that describes how Native Americans roamed Portage County freely. Christian Cackler, an 1816 settler of Franklin Township, one of the earliest settlers in the area, penned Recollections of an Old Settler in 1874. On page 3 of the opening chapter, he describes several eyewitness experiences of how Native Americans flourished in Portage County. He writes that there were approximately 40 Native Americans for every white man and primarily focuses on his observations of Seneca Chief John Bigson who lived on the land now known as Streetsboro.

Before he died, I spoke with local historian Roger Di Paolo on the issue, and while he agrees that much of Portage County’s native heritage is “written from the perspective of white historians with inherent biases,” he directed me to Portage Heritage, published in 1957 by the Portage County Historical Society. This work includes a section on Native American life before colonization, including a section entitled “Burial Mounds Numerous.”

These texts prove that indigenous life existed in this area. However, each of these sources comes from white settlers, has several culturally insensitive designations for Native Americans, and views them as archaic, cultural relics that are lost to the past. So, I tried to find a source that is more appropriate.

To be sure what I was researching was true, and to remain in solidarity with indigenous people, I spoke with Sundance of the Muskogee Nation, the executive director of the Cleveland American Indian Movement.

I asked Sundance specifically if he might know anything about this mound that was destroyed in Randolph’s early history, and what group might have established it. In this way, we could be more accurate and inclusive in our statements regarding the settlement of the township. In my correspondence with Sundance, he said, “The term ‘Moundbuilders’ is shorthand for a specific group of people; however, it is highly likely that their name is lost to history.”

So, while we might never know what tribe to specifically honor after the desecration of their mound, we can at least learn a little bit more about Portage County’s connection to pre-colonization Native American tribes. The Portage Path, for example, was integral to the foundation of this area.

The Portage Path had two cosmopolitan towns at each end, but according to Sundance, “the identities of those peoples should not be confused with the people who built the mounds; in most cases the descendants of those specific moundbuilders in Ohio cannot be identified (which is why that term is almost universally used).” Sundance also mentioned that historical accounts of indigenous groups before European settlement are “scarce,” because “by the Great Peace of Montreal (1701), most of the original inhabitants had been displaced by Iroquois aggression.”

He said the Portage Path was “an eight-mile stretch connecting the Cuyahoga and the Tuscarawas Rivers, making it possible to travel all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. It was greatly utilized.” As a result, “the villages of Cuyahoga and Mahoning, both on their respective rivers, were occupied by Delaware from 1758 and 1756, respectively, to about 1778.” Around 1810, that land (Cuyahoga) was then occupied by the Seneca.

Later, I asked Sundance what tribes specifically might have lived in the area during early settlement. He said that “on the Cuyahoga River end of the portage, there were Mingo, Delaware, Abneki, Potawatomi, Ojibwa, Wyandot and Ottawa peoples, along with others I might have left out.”

Although we will never know the names of the people who built the burial mound in Randolph, there are still ways to memorialize the desecration of this early structure. Maybe a plaque or land acknowledgement of some sort could be dedicated to honor those who were here before us. Despite this unfortunate reality, there is still more to learn concerning Native Americans who lived here during the settling of Randolph.

“The short answer to your occupation of Portage County would be Delaware in history and unnamed mound-builders in pre-history,” Sundance wrote. “Until 1656 that land (Randolph) was Erie territory, although it was likely occupied by other small bands.”

Now, when we think about Bela Hubbard, we can now include the likely specific groups whose land we stole.

We need to reconsider the history of the land we currently occupy. Most residents learned about Native Americans in Ohio in elementary school, and those histories are often taught in relation to settler history. Rather than viewing this group as archaic relics, we need to recognize they still exist. These local examples of their existence can be a step in the right direction toward acknowledging this.

We can take the step in addressing racism toward Native Americans by learning more about their culture, language and why issues like having offensive mascots are wrong. Hopefully, this information can serve alongside the historical narratives of Randolph, and will spur others to research about other small townships as well. It is the first step in learning the truth behind the dark history of our current settlements. Now knowing this information, one thing is clear: We all need more accountability, and need to acknowledge this nation’s indigenous history.

Consider supporting a local Native American organization, such as donating to the Cleveland American Indian Movement.

Anthony Catalano is a graduate of Waterloo High School and Kent State University. He lives in Randolph.