Recently I’ve been fascinated by memoirs. (You’ll see why at the end of this column!) These all happen to be written by women; I thought I would relate to them more than to those written by men. I’m not sure I did, but I learned something from each of them.

Among these books, the one that probably made the most impact is “Corrections in Ink” by Keri Blakinger. The author grew up in an all-American, upper-middle-class family with caring, supportive parents. She was a bright student and a talented figure skater with a promising future, but she couldn’t handle the stress. “For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a dark side. I tried to kill myself for the first time in my mid-teens. … Before that, I dabbled with cutting, but instead settled on starving myself,” she writes.

Then she discovered drugs and made horrendously bad decisions. She found herself stealing, selling drugs, selling herself, landing in and out of jail. And her experiences in jail … whoa. She tells us, “About doing time: you’ll always be scared.” The language is rough. The images are rough. What happened to her and her jailmates is rough.

She related to her fellow inmates: “We’d all landed behind bars because of our addictions.” She describes the general horrors of being behind bars and the specific horror of solitary confinement, which she calls torture. “Some people handle it just fine, and others deteriorate slowly. … I began to see how broken the system could be, and how much it could break a person.” She dealt with bullying guards and even bullying counselors and realized that “All the futility, the small cruelties, the refusal to see us as fully human — it was not a flaw in the system. It WAS the system.”

Eventually she got straight, served her time, and became a journalist specializing in prison reform. The writing is good, but her story jumps forward and back in time, leaving the reader a bit discombobulated. But it’s a powerful cautionary tale: Drugs will own you.

“The Community” by N. Jamiyla Chisholm is the account of her childhood years spent in a cult in New York.

In 1978, she was only 2 when her parents moved into the Ansaaru Community, which turned out to be a separatist Black Muslim cult. Her father believed in the teachings of Malcolm X and thought Ansaaru and its charismatic leader offered Malcolm’s vision of freedom. He converted to Islam and persuaded his wife to do the same; then he convinced her to move with him and their child to the closed society.

They left behind almost all their possessions. The child was put in with other children, the mother with the other women. The women were “covered from head to toe in yards of fabric.” There was no privacy.

“Everything was controlled.” She remembers, “In this Community, there were no toys, no noise, no color.” There were “about thirty other girls around my age in the room. We were all mirrors of each other, dressed in the same attire.” The women were cruel and abusive to her and the other children.

Her mother soon “knew she was in over her head but was too proud to back out so soon. Plus, the thought of losing her family, of my father not standing with her, terrified her.” One of the other women told the mother, “You have to have an open mind, or this won’t work. … This ain’t supposed to be easy.”

After a couple of years, her mom finally gathered the courage to leave with her daughter. But the mess didn’t end there. It turns out, her dad was a piece of work. So was the cult leader, York, who was eventually arrested for child molestation and sentenced to 135 years. “York’s predatory ways, his schemes to rob families and lord over lives, was such a classic case of narcissistic-psychopathic crazy that I find it difficult to believe no one saw it.” For some former community members, “he remains a god, even while in prison for the rest of his life.”

But, she explains, “I can understand why they were attracted to York and his branded message of Islam. York told them they were beautiful, intelligent, worldly people who didn’t have to put up with being second-class citizens. He showed them power.”

You know I had to read a book with the title of “Bookends: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Literature” by Zibby Owens. Owens is a frequent talk-show guest and the creator of the podcast “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.”

She writes about how much books have meant to her throughout her life, starting at the age of 8, “A little girl in her cotton nightgown hunched over a book, motionless yet completely moved” by reading “Charlotte’s Web.” “That night, I was hooked. Yes, I was already a bookworm.” She tells us, “Books, for me, are lifesaving. They have been my companions, my teachers, my entertainment, my emotional outlets, my escape. … I can recount exactly where I was when I read almost all the important books in my life. Many books came at just the right time.” Oh, yes, I can relate to that.

She goes into her family history — “At the root of our story is the American Dream” — and admits she’s the child of privilege. She shares anecdotes about her drinking problems, eating problems, family divorces, her two marriages, and having kids. But really, the heart of the book is taken up by the important people in her life, including her best friend, who was killed in the 9/11 attacks in New York. Then more people died; I lost track of the number. Good heavens, almost everybody dies in this book!

She mentions SO many book titles! No, I can’t relate to her wealthy privilege, but I definitely found her reading list impressive!

Finally, two books by Korean Americans focus mainly on the authors’ mothers.

In “American Seoul,” Helena Rho describes the “cultlike conditions of being raised by an immigrant Korean mother with major depression” and the “nightmare of marrying an emotionally and physically abusive man.” She also discusses “being sexually harassed on an almost-daily basis as a medical student” and “being racially discriminated against by my fellow doctors and the institutions that hired me.” Wow. Full plate.

She was a pediatrician who never wanted to be a doctor: “As a good Korean daughter, I had felt obligated to go to medical school to please my immigrant parents, to fulfill their American Dream.” Also, her mother told her, “Of course you must marry Korean. It is who you are.” So, naturally, she didn’t.

Her dad was hardly ideal: “Because my father helped raise me, I learned that fathers did not necessarily love their children. … And I learned to expect that a husband would be selfish and careless and leave his children behind, with little expectation that he would support them either emotionally or financially.” Enter her abusive, “narcissistic sociopath of an ex-husband” who, even after the divorce, ended up “trying to destroy me” emotionally, mentally, and financially.

When an incident awakened the memory of her childhood sexual molestation, she recalls that all her life she had “swallowed the shame …, as if the violence had never happened. I shut it up inside a part of me that would not acknowledge what had happened until I was fifty years old. I thought that by not acknowledging it, I would be fine.” She says, “I didn’t know then that my body remembered the trauma while my mind rejected it.”

“Crying in H Mart” by Japanese Breakfast singer/guitarist Michelle Zauner has become a bestseller.

Zauner explains that “H Mart is a supermarket chain that specializes in Asian food.” It’s important to her because “Food was how my mother expressed her love.” Every other summer she and her mother would visit family in Seoul. “I loved visiting Korea,” she recalls, relating many anecdotes of Korean culture.

Living in Oregon, she says, “I didn’t have the tools then to question the beginnings of my complicated desire for whiteness. … I felt awkward and undesirable, and no one ever complimented my appearance.” But she made “a pleasant new discovery: I was pretty in Seoul.”

The tragedy, she writes, was that “Within five years, I lost both my aunt and my mother to cancer.” Taking care of them during the illness, she explains, “I wished desperately for a way to transfer pain, wished I could prove to my mother just how much I loved her, that I could just crawl into her hospital cot and press my body close enough to absorb her burden.”

She tries to learn how to create Korean dishes her mother will eat, when the chemo steals her appetite. Oh, there’s a lot of food in this book! Some of the culinary choices are alarming (live octopus, really?).

After her mother’s death, she tells the reader, “Sometimes my grief feels as though I’ve been left alone in a room with no doors.”

The writing is good, and the Asian cultural information is interesting.

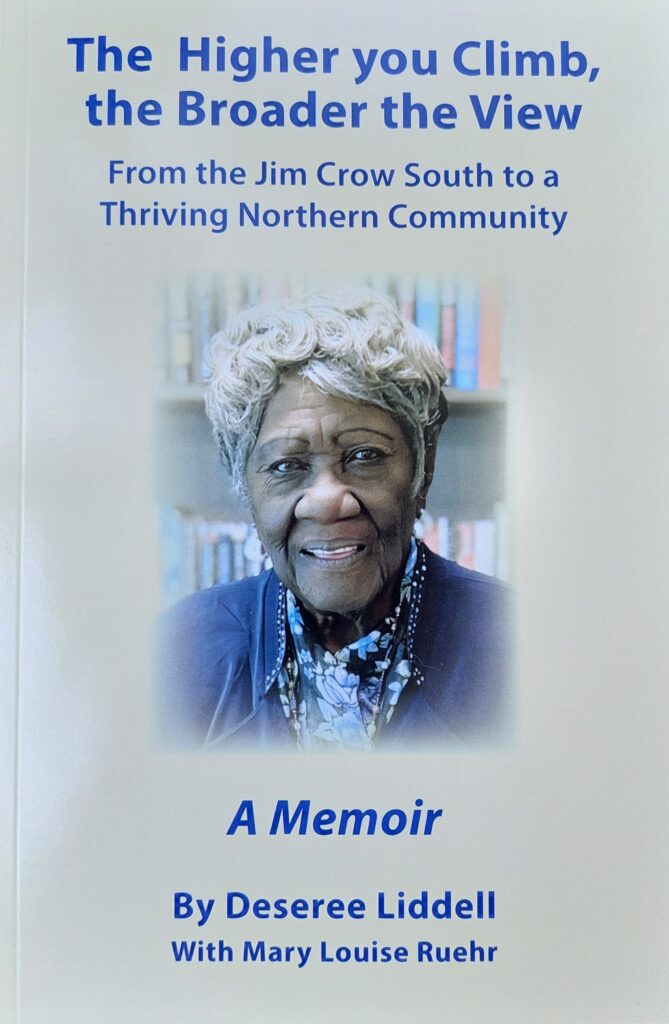

Oh, and the memoir I’ve been working on for several years is finally available. It isn’t my story; it’s the memoir of Mrs. Deseree Liddell of Ravenna, titled “The Higher You Climb, the Broader the View: From the Jim Crow South to a Thriving Northern Community.”

Deseree Liddell’s life has been remarkable. Now 96, she looks back on her childhood in Mississippi, one of the worst places to be during the Jim Crow era. Some of her experiences may make you angry; some may make your hair stand on end.

As a young woman, she spent time in Chicago, where she felt more freedom than she’d ever known before, but went back to Mississippi to teach. There she met her husband, with whom she eventually moved north to Ohio, settling in the Ravenna community of Skeels. There she ran into still more discrimination and had to fight for the simple basics of life.

The book is available from Skeels Community Center for $20 plus $5 postage and handling. Proceeds will go to the Deseree Liddell Minority Scholarship Fund. For more information, write to [email protected].

Also, Mrs. Liddell will appear at a book signing from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturday, Aug. 6, at the Skeels Community Center, 4378 Skeels St., Ravenna. Maybe I’ll see you there!

Happy reading!

Mary Louise Ruehr is a books columnist for The Portager. Her One for the Books column previously appeared in the Record-Courier, where she was an editor.