In mid-March of 2020, some of us in Portage County were wondering if we might be dodging a bullet.

While counties to the north, south, east and west of us began reporting multiple Covid cases, Portage had yet to report a single case.

But then at the end of the month, as the daffodils were coming into full bloom with the lilacs beginning to bud, Portage County lost its first victim to Covid.

Lifelong Ravenna resident Lavern F. “Bob” Ferrell, 90, died a year ago today, on March 29, after contracting Covid in the nursing home where he lived.

We knew then we were not so special, as we watched Covid begin to take its toll in our county, too, as we became afraid for our lives like everybody else, crossing the street to avoid our neighbors, making masks out of T-shirts, sequestering in our homes.

By the end of a 12-month period, more than 11,715 people would show positive for Covid in Portage County, and 192 would die.

In my house in Kent, we were already no strangers to avoidance of germs.

I had been diagnosed in 2009 with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), essentially cancer of the immune system.

My family already knew not to allow friends in the house with so much as a cough and to wash their hands like their mother’s life depended on it.

Now we were all that and then some, as one-by-one the normal activities of our lives disappeared, and we moved into a three-person bubble.

My youngest child, 22, a Kent State senior living at home, was most deeply affected, as first the university switched to online classes, then his sports groups disbanded and the play he was in was canceled. Because of my health, Benjie could no longer keep his restaurant jobs, not even doing delivery.

As for our other housemate, Benjie’s brother, 31-year-old Chris’ life turned upside down in January when he moved home from Washington, D.C., to help with family matters. He was continuing remotely with his D.C. work, but his bustling life was otherwise reduced now to being with me and his little brother in our little Cape Cod on the cul-de-sac in Kent and going back and forth to Stow to be with his Dad.

As for me, my photography business came to a halt. I continued to write as a freelance columnist; every column for the next year and ongoing would be about Covid. So much to write about: how to stay close to the ones we love, how to stay sane in the midst of ongoing trauma.

In many ways we were no different from families all around us, each of us struggling with our own specific circumstances. We supported our friends as they juggled jobs while trying to homeschool children. We watched as Kent Social Services saw a surge in needs, and responded by helping with a fundraiser that raised $10,000.

The stress was inordinate for all of us, compounded for me and others with immune-compromised systems, by the fear that a Covid infection could kill me.

Further stressing me was pressure from my doctors, who wanted me to start a leukemia treatment regime. Knowing the drugs came with their own risks, that they would further compromise my immune system, I said no. My decision kept me in a constant internal battle, wondering if I was killing myself or keeping myself alive by my decisions, even as Covid raged outside.

Ever a believer in self-care, I did what I could to mitigate the anxiety and to try to maintain and even recover my health: I kept meditative coloring books by my bed, took walks around the neighborhood and tried to eat well. I Zoomed with friends and my sisters in other states and engaged in virtual consults with my therapist. A former Catholic and Episcopalian, now a sometimes Unitarian Universalist interested in Buddhism, I also printed out prayers from every religion to keep in a stack on my bedside table. I joined prayer groups and began to meditate more intentionally and deep-breathe for sometimes several hours a day.

As much as anything, I kept focused on the family.

Family was always my default, and it was no different now. I already knew maintaining life’s primary source of love was paramount to my sense of well-being.

It was possible, even, that this was a singular opportunity, to better my now adult relationships with my children against such an intense backdrop.

This wouldn’t be easy given that my two housemates were millennials and I was the lone Boomer.

My sons had their own ideas now about how to do things, which they were eager to try out. Rules around how best to clean the kitchen — whether to clean the kitchen? — were up for grabs. Now here, too, was Mom, demanding the most stringent of safety precautions, even if they were more extreme than their friends’, some of whom were still hanging out maskless with friends. At one point, a Covid moment we all hate to recall, I had to insist they live in the basement because they’d been exposed to a friend who might have had Covid. There would be a week of me leaving meals at the top of the steps before we would find out their friend was Covid-free.

Like other families in bubbles, we found ways to interact beyond Covid. We set up croquet in the front yard. We karaoke’d together on Friday nights. We cooked together, played board games. We also had hard conversations. “You know if one of us ever gets sick, we will have to go to the hospital alone,” I figured I had to say at one point. I created recordings on my phone of the kids interacting; in case I ever had to go to the hospital, I would have these recordings to comfort me.

While we did what we could to adjust, individuals and businesses in Portage County also adjusted. Restaurants dropped to delivery and takeout only. Kent Natural Foods went to curbside, a service that, thankfully, the store still makes available a year later.

These parameters, as established by the governor, were not without conflict, too. Not everybody thought restaurants, bars and schools should close. People couldn’t even agree to wear masks. Students in Kent were often seen in the front yards at the frat houses on University Avenue, tossing footballs and Frisbees, gathered around kegs, unmasked.

Not being on the same page with safety, not knowing whether we were protected when we walked outside, added to the stress and fear, as numbers continued to rise: By late-May, the United States had surpassed 100,000 deaths, 2,002 of them in Ohio.

And then, on Memorial Day weekend, the world watched as a white police officer killed a Black man in Minneapolis in plain view of video cameras.

The eruption around the death of George Floyd was unprecedented as fed up and traumatized throngs took to the streets throughout the state and the world. We activated in Kent, as priorities shifted from keeping ourselves alive to fighting for the lives, rights and well-being of others.

Stress, suffering, pain and conflict were everywhere, it seemed.

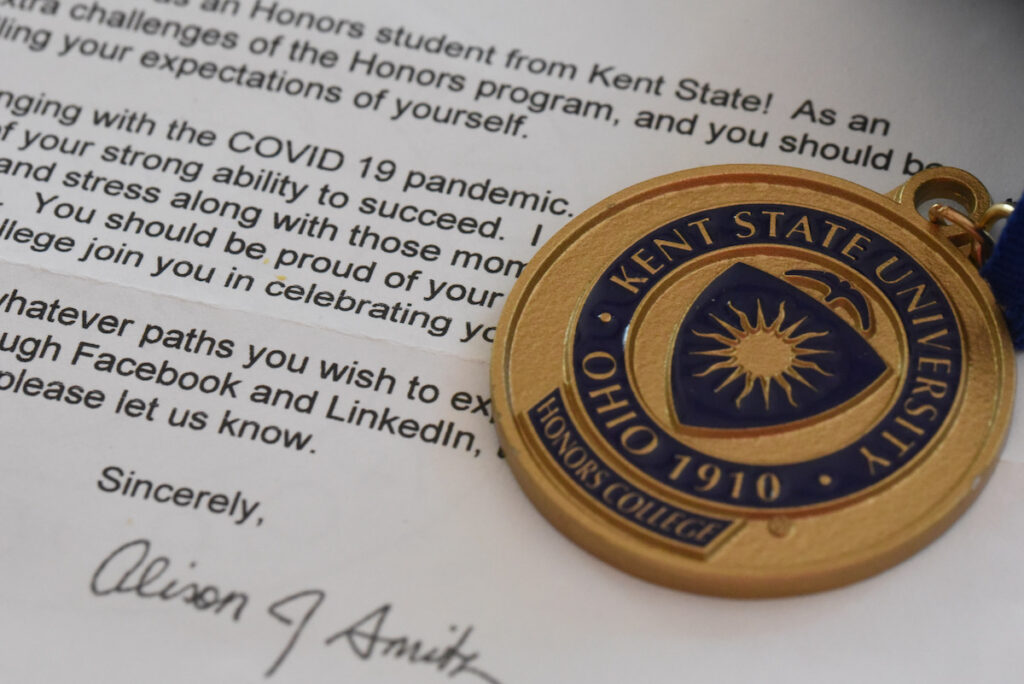

In fact, I’m dumbfounded now, to look back and see how human life went on, at least according to photos on my Facebook page: I see that I duplicated my mother’s Easter basket cake like I do every year when Easter Sunday comes around. Benjie graduated from Kent State a week after Easter, albeit in the kitchen, while listening to a virtual ceremony. I see pictures of us marching for racial justice, pictures of us saying good-bye to Benjie as he moved to Colorado in July with his new AmeriCorps job, pictures of Chris’s new puppy. We even had a somewhat normal Thanksgiving and Christmas, albeit socially distanced. This was even as our country faced down another national crisis — a contested presidential election that became a source of contention and violence.

Throughout this time, the pandemic continued, with a frightening surge during the holidays. As the year ended, the United States surpassed 20 million infections and more than 346,000 deaths. Globally, cases rose to 84 million and deaths to 1.8 million.

Looking back at the year now, I count our family lucky in so many ways. While we know people who lost family and close friends to Covid, we did not directly face a death or serious consequences from the disease. I also did not have to go this alone like so many of my divorced, separated and widowed middle-aged friends; one or more of my children was always here, including now my 28-year-old daughter, who also moved home from Montana to help.

Looking back at the year, I also see at the top of one of my journals a question that can still perplex me: “Is it better to be hopeless?”

It is a concept proposed by Pema Chodron’s book, When Things Fall Apart, which I read with a group of friends last year.

Sometimes, the point is, she says hope can be false and keep us from facing reality.

There’s a fine line, I think I see now, as I watch people let up their guard while living into the hope of vaccinations. It is hopeful that, as of the end of this month, 28% of the Ohio population had received at least one dose of a two-part vaccination. And many more are in line with appointments. But this is not the full measure of reality. Covid is still out there and going strong.

Meanwhile, there is the unequivocal hope of such things as spring. There is the hope of a new, freshly painted, free miniature library on the corner of Doramor and Dansel that a neighbor’s family built. There is the hope of people being extra nice to each other, it seems, on the phone during service calls, at the grocery store when I pick up my groceries.

“Stay safe,” we end our calls to each other.

For many, there is today the promise of Holy Week and Easter.

I think of Easters past as I prepare to make my mother’s cake again, as I think of my mother making Easter dresses for me and my three sisters, as I think of all the ancestors who came before her, strong people who weathered Ellis Island, their own pandemic in 1919 and two world wars.

I think of the power and strength of all of us, all the front-line workers who not only tended people on their deathbeds but also nursed many, many more back to health at the risk of their own.

On my dresser is a rock that a secret someone put on my front porch in the spring of last year.

“Resilience,” it says.

I look to this.

I look to my family.

I look outside my window every morning for the coming of the lilac, and the daffodils, blossoming anew.

Debra-Lynn B. Hook of Kent is an independent journalist and photographer, a backyard gardener & the mother of three children.